If you can remember Matt Taylor, that bloke who fronted Aussie blues outfit Chain in the very early seventies, you will recall him as a beery, beardy growler; as far removed from the stardust world of glam rock as is humanly possible.

In the summer months of 1973/1974 one of the local AM radio stations began promoting a Memorial Drive gig, that they labeled ‘The Survivors Concert’, and Taylor was announced as one of the headliners, along with Daddy Cool, Ariel, Brian Cadd. These heavyweight acts were to be supported by a local group, Perelandra, named after a C.S. Lewis science fiction novel, which was cool, but who, annoyingly, as a band were not, as they had a flute as one of their lead instruments.

It was a first-rate line-up, and I wanted to go, so I asked my mother.

She said I could – as long as I had some friends to accompany me, so I gathered a small group of intrepid thirteen year-old warriors together, all whose parents reluctantly said yes without too much trouble, and we bought our tickets.

I had the beginnings of a pretty eclectic record collection at that time; a smattering of sixties 45’s that were hand me downs from my sister, The Archies, Joe Cocker, Doug Ashdown, Jesus Christ Superstar, and, most recently and most excitingly, David Bowie’s ‘Ziggy Stardust’ album, the acquisition of which had become a recent life-changer.

I also had Matt Taylor’s single, ‘I Remember When I Was Young’, which had been a top ten hit only a few months earlier. There were others too, and the collection was growing in a haphazard way that bemused my friends.

Source: http://www.45cat.com

I was not an elitist, someone who mined one genre and spurned all others, so saw no issue with mixing my tastes in this way – but others did and regularly paid me out for it.

In the days leading up to the concert, I became unusually concerned about what I would wear. I decided that I wanted to wear a Matt Taylor shirt, and promptly wrote his name in big block letters on the front of a white Bonds tee, using a thick black texta. The letters were uneven and the name ended up skewed a little too far to the right.

To my eyes, though, looking in the mirror, it looked about right. It would do.

My sister did not agree with this appraisal, however, and, after quelling her laughter, suggested she sew some sequins on the lettering to at least try and cover up some of my poorly drawn curves and flourishes.

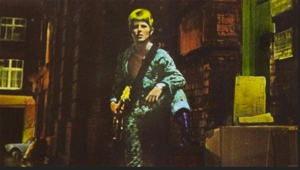

Hence, Matt Taylor, check-shirted, Levi wearing macho icon, a man whose latest album was entitled ‘Straight As A Die’, was to be represented as some sort of glitzy glam sparkly entity by the dazzling gleam of his name across my chest, and, as I strode in through the gates of Memorial Drive on my way to giving praise to The Survivors of Oz rock, heads turned. Job done nicely, I thought, misreading their incredulous stares for jealous awe. The shirt, I fervently believed, nicely complimented the denim jeans tucked into the knee length maroon vinyl boots that I had stolen from my sister’s room. To my eyes, these boots were reminiscent of those worn by Ziggy Stardust, the supreme being, on the album cover I had been spending so much time staring at recently in my room.

Ziggy putting his best boot forward.

Photo: Brian Ward

Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk

I think the concert was good, although I remember little of the music. What I do remember was meeting Gabi, a freckly high-spirited girl, two years my senior who was there with a couple of her equally excited friends.

I lied to Gabi about my age, saying I was seventeen. She believed me. I also told her I rode a motorbike, and quite a few other tall tales designed to impress her.

At one point during Daddy Cool’s set, I let her climb up on to my shoulders and bounce up and down to the beat for a few songs. Below her oblivious joy, I was breaking into a sweat, my legs screaming to be allowed to collapse, and my heart straining to maintain the effort to keep her aloft, but I was determined not to embarrass myself by showing any physical weakness, so I focused on how pleasant her warmth felt on my bare neck, and how smooth her skin was under my hands where I held her calves.

After the concert we kissed in the car park, and thankfully then she had to go because her friends’ parents were in their car just down the road, and she couldn’t keep them waiting. This spared me from having to say the same thing about my ride home, also parked somewhere down the road, but in the opposite direction.

During the evening I had told her that I was in my final year of school and had not lied about where. This rare moment of honesty, in the long run, would prove to be a terrible mistake on my part.

Some weeks later, whilst I was engrossed in botching up yet another spoon in first year Woodwork class, one of the older boys came in to the workshop and said there were a group of girls at the school gate asking for me. I put my hand up and told the teacher I needed to go to the toilet and headed out to the gate wondering who it could be who wanted to see me.

From a distance I recognized the girls. It was Gabi and her friends from the concert. They had skipped school and caught a bus out to see me. When they saw how I looked their expressions became puzzled. I was wearing my uniform – shorts and shirt and scuffed Bata Scouts – and looked even younger than I was, I am sure.

‘How come you’re wearing a uniform?’ Gabi enquired, not unreasonably. She was dressed enticingly in a boob-tube and hot-pants.

‘It’s optional here’, I said, ‘and my jeans are in the wash.’

‘Where’s yer motorbike?’ one of her unimpressed friends asked.

‘Oh, I’m banned from riding it to school, I rode it through the school yard last week and terrorized some of the little kids. So I put it into the shop to have some detailing done on it.’ I had no idea what I was saying.

‘So, you wanna ditch school and take us back to your place?’ Gabi asked.

‘Err…OK, sure’, I mumbled, ‘but you’ll have to wait awhile, I have to finish off something first.’

‘Yeah, OK, we’ll wait.’ Gabi climbed up on the school fence and sat in a provocative pose smiling at me, ‘Don’t be long…’

I had never wagged school before, but every kid knew of a foolproof way to get sent home.

The school’s bursar, an ancient woman devoid of any sense of humour, and who had what looked like a large boil growing out of her head through her hair, doubled as the school’s nurse. One condition she would not countenance was diarrhoea, and we all knew that if you successfully created the illusion you were suffering from it she would sent you home immediately, without any further investigation of your state of health.

I went back to Woodwork class and waited a few minutes before putting up my hand and asking to return to the toilet.

‘Didn’t you just go a few minutes ago?’ the teacher asked.

‘Yes, but I think I may have diarrhoea, sir.’

‘Really? Well then you better go and see the nurse after you‘ve done your business.’

Ten minutes later I was walking across the playing fields adjacent to the school, with my arm around Gabi’s waist, heading towards my place where I knew no-one else would be home.

Gabi was impressed with my father’s gold velour recliner – especially its two-speed electric vibrating function – and was keen for us to cuddle up on it. Her friends diplomatically retired to the kitchen and listened to the radio, turned up loud, until we were ready to rejoin them.

Soon, the girls had to leave in order to have enough time to get them back to school before their parents’ afternoon pick-up. I walked them to the bus stop, gave Gabi a long passionate kiss, and said I would go with her to the football on the weekend. We agreed to meet at Unley Oval where we would watch Norwood play Sturt.

That Saturday, I took the city bus and then walked through the South Parklands, up Unley Road to the oval, where Gabi was waiting for me at the gate, as arranged. We walked arm in arm into the ground.

The game was close and the crowd was often loud and boisterous. From time to time I felt myself being hit by objects hurled from the crowd behind me – a bottle cap, a screwed up Balfours’ bag, a bit of pie crust. I looked back a couple of times and saw some leather-jacketed lads scowling and roaring at the umpire, but one of them was looking straight at me and he snarled.

At half-time, I broke free from our embrace and my intoxication with the smell of her hair, and declared with great generosity and chivalry that I was going off to buy my lady a drink. I pushed through the crowd and made my way slowly towards the kiosk.

Looking ahead, through the jostling punters on the path, I saw the intimidating form of the leather-jacketed hoon who had growled at me earlier. He was coming towards me from the opposite direction. As we passed, he deliberately bumped into me with some considerable force, and tried to knock me into the spectators seated with their just opened vacuum flasks and unpacked sandwiches. I kept my feet and kept going, shaken, and not understanding what the guy’s problem with me could possibly be.

When I returned with my liquid offerings, I suggested that we find a better vantage point to watch the second half of the match. Gabi said she would do whatever I wanted.

Moving to a new spot was fortuitous in one respect because we both bumped into people we knew, and I relaxed a little knowing that there was strength in numbers.

After the game, a group of about six of us made our way on foot back to the city. We were soon walking along King William Street happily heading towards Victoria Square, when an EH Holden screamed to a halt on the opposite side of the road to us.

A man got out, brandishing a beer bottle, and shouted: ‘When I catch you, I’m gonna bash your head in!’

Everyone stopped, apart from me as I had recognized the leather jacket, and it was soon obvious, as he changed direction to track my continued movement, that his threat was specifically directed at me.

I broke into a sprint and he accelerated too. I raced towards Victoria Square because I knew the main Police Station was there. By the time I reached the entrance he was only a few metres behind me. I threw open the doors and yelled, ‘Someone’s trying to kill me!’

No-one in the police station seemed too concerned. In fact, initially, they ignored me. I slumped into a seat and drew my breath in, sucking in air in wheezy gasps. After some time, I went to the window. I could see my assailant, now across the road in the square, standing stock still, fixedly staring back at the police building. I sat down again, and waited.

After some time, a police officer came up and asked me what the problem was. I recounted my story. He nodded a few times, said I could sit there and wait for as long as I wanted, and that the guy would eventually get bored with waiting and leave – sooner or later.

I waited for about an hour. Then I gingerly opened the door to the street. I could not see him, but I could see that Gabi and our friends were waiting for me on the grass across the road.

‘He hung around for about half an hour and then left’, Gabi told me, ‘I think I know the guy. He used to go to my school. He likes me.’

We walked to her bus stop and performed our now prolonged, well-practised, physically exhausting goodbyes.

Once I was safely home I decided that this relationship was too dangerous to continue, and that I would not contact Gabi again.

She rang me some days later, wondering why I had not been in touch. I told her that I did not want to see her again. She cried for awhile before she hung up the phone.

A week after this call, I received a letter from her. It was written in lurid pink and green fluorescent texta colour. She called me every nasty name you could imagine, then she gave over pages to her friends to write so that they could call me every nasty name that they could imagine too, and then she listed the gangs who had been given my details with an edict to bash me on sight: the Norwood Mafia, The Payneham Boys, and three or four other associations devoted to aggro.

I was worried. For days I could not sleep or think about anything else. I finally showed the letter to my mother and told her the whole sordid tale. She gave me the expected lecture and promptly composed a letter to Gabi’s parents threatening legal action if any further correspondence was ever received from the girl, or worse, if any harm should befall upon me.

It was a lie, of course, we could not afford any legal assistance, nor could she call upon anyone to act as muscle, but it seemed to do the trick, and I heard nothing of her again for many years.

For quite a long time, I was very reluctant to go into the city for fear of my face being recognized by any of the gangs who supposedly had me at the top of their hit-lists, but, over time, this apprehension passed and life got back to normal.

Gabi and I did meet again, however, one day, when I was eighteen.

I had just been to get my travel inoculation injections, and I was coming down in the lift of the ANZ Building with half a dozen other people, when two women in their mini-skirted work uniforms got into the lift at one of the lower floors. Their arrival made everyone squeeze up tighter, and through the forest of necks and shoulders, I could see, with a sudden jolt of recognition, that one of the new arrivals was Gabi.

She was looking straight at me. I tried hard not to let on that I had recognized her. Gabi brought her hand up to her mouth in order to shield her words as she whispered to her workmate. The other woman turned and subsequently looked at me too.

At ground level, I hastened to the main exit, but both of them followed me out and up the street, then along the Rundle Street shopping strip. They kept close behind and tauntingly called my name repeatedly, laughing at me. The faster I walked, still pretending that I had not seen nor heard them, the faster they followed.

I was having an internal conversation with myself, wondering why I was feeling such panic, rationalizing my fears, trying to convince myself that the threats from five years earlier were toothless, and that they had been blown out of proportion by my fertile thirteen year-old imagination. The taunts from behind me kept coming though, and I began to see passers-by raising their eyebrows as they recognized that something odd was going on.

Quickly and unexpectedly, I turned into the Harris Scarfe store and hid myself amongst the racks of women’s clothing. I heard their voices in the store for a few moments, Gabi expressing her liking for a pretty sequined blouse – ‘Look at it sparkle in the sun!’ – before her friend said they better hurry and leave or else they wouldn’t have time to eat lunch. Through the chiffon and lace I saw them walk out into the street.

Once again, I found myself taking some time to pluck up the courage to leave. A saleslady came up and asked if she could help me.

How could I answer that?

I summoned up some dignity, stood up straight, and walked out of the store.

In the sun, the spot on my arm, where the injections had been given, throbbed, reminding me that, by now, I should have been immune to most things.

Very enjoyable reading. Particulary like the stories from “your” youth, feel we must be in the same age bracket as can relate to so many of your recollections during the 70’s. You certainly have a gift for writing. Thankyou for sharing it and I will look forward to reading more! Cheers, Lorna B

LikeLike